In the spring of 1967 a young

couple on vacation from their work in Washington D.C. were exploring Bogue

Banks. She was showing him the area where her Grandfather once had a fishing

cabin. Turning off Salter Path Road at Juniper, they drove north on what at the

time was a packed dirt road sprayed with tar-oil to keep the dust down. Going

left when the road ended at Oakleaf, they proceeded a short way until the road

ended at what is today McNeill Park. They left the car parked at the end of the

road and explored the construction activity underway. A canal was being built

by the use of a crane-type dragline. This inquisitive couple recalls a

cofferdam near the canal’s north end to keep Bogue Sound from filling the

construction site. Pumps were also operating to remove seepage and naturally

occurring water.

This eyewitness recollection

sparked my interest to learn more about the building of the Pine Knoll Waterway

. . . Oh yes, that couple lives today in Pine Knoll Shores.

In the 1960’s building a

canal system as part of a real estate development was a common practice up and

down the east coast. From a

governmental regulatory perspective, constructing a canal system in the late

1960s and even the marinas at Beacon’s Reach and Sea Isle in the 1980s was

significantly easier than it would be today. What with environmental

sensitivity, wetland designations, wildlife and endangered species concerns,

plant and habitat issues, water table and waste water disposal and ground water

contamination considerations, the requirement for Environmental Impact

Statements, and other county, state and federal regulations it would be a hard

slog to develop a community today with similar amenities to what we have.

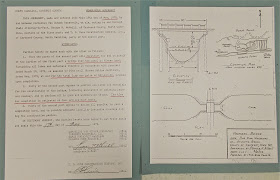

The above illustration

appeared in the July 1967 issue of Our State magazine discussing the planned

community being developed on Bogue Banks.

The above illustration

appeared in the July 1967 issue of Our State magazine discussing the planned

community being developed on Bogue Banks.

In Pine Knoll Shores the

canal system was built to address several problems and to create a number of

attractive conditions. Eliminate the negative and accentuate the positive.

The Problems: North from the dunes along the ocean, the

land was mostly low-lying. In 1998, Don Brock spoke at the town’s twenty-fifth

anniversary celebration. He recalled that when he first came here in1965, his

initial reaction was “This is just a swamp, it has to be drained.”[i]

The water table, before the canals and marinas were built was quite near the

surface. So much so, that the early houses built in the late 1950s could get

water by use of shallow wells.

The second problem that had

to be attended to, to enhance the attractiveness of the area, was mosquito

mitigation! Some early property owners considered this locale fine for a place

to come in the winter, but in the summer the mosquitoes made it intolerable.

County and state health officials were sensitive to threat posed by mosquitoes

in any low-lying, wet area, and often withheld development approval until

abatement actions were taken.[ii]

The Positives: The route of the waterway took advantage of

some existing low ponding areas; the spoils from the digging were used to fill

other low areas. An early resident, who lived on Cedar Road recalled walking cross the tidal creek that existed before the canal was built. Perhaps it looked simular to the creek pictured below which is located in the Roosevelt Natural Area.

This approach eliminated swampy swales that held water after rain and were mosquito-breading grounds. Additional spoils were utilized to raise the general level of the surrounding ground and roadways. These actions contributed to other advantageous consequence – The canals in effect lowered the ground water level improving the functioning of septic systems, it also allowed rainwater to drain without the need for roadside ditching, a common sight in low country regions.

This approach eliminated swampy swales that held water after rain and were mosquito-breading grounds. Additional spoils were utilized to raise the general level of the surrounding ground and roadways. These actions contributed to other advantageous consequence – The canals in effect lowered the ground water level improving the functioning of septic systems, it also allowed rainwater to drain without the need for roadside ditching, a common sight in low country regions.

The canals in Pine Knoll

Shores, official name Pine Knoll Waterway, were constructed in two phases. Pictured above is the east half running from McNeill Inlet to Mimosa Blvd[iii].

This phase was completed in 1967; it included Hearth’s Cove, King’s Corner arm

and Hall Haven marina. At the opening of

that phase the waterway was advertised as being 80’ wide and 8’ deep.

The second phase of the waterway was completed by 1971 and ran west from Mimosa Blvd. to Hoffman Inlet

and included Davis Landing, Hopper’s Hideaway, and Brock Basin. After the two parts of the waterway were

completed a bridge at Mimosa Blvd was constructed and the waterways two parts

were connected, thus allowing full circulation of water throughout the

waterway.

The East side of the waterway

employed a crane-mounted dragline as the primary construction approach. A crane

working from each side of the planned route of the canal would provide improved

directional control and speeded up the process. Whether one or two cranes were

used the operation would have been the same.

In a typical cycle of excavation, the bucket is

positioned above the material to be excavated. The bucket is then lowered and

drawn so that the bucket is filled by dragging along the surface of the

material. The crane hoist then lifts the bucket. The crane is then pivoted to

move the bucket to the place where the material is to be dumped. The material

is deposited along the banks and the crane then moves forward on the mechanized

treads.

A skilled operator could throw or cast the bucket, swinging the

bucket like a pendulum. Once the bucket had passed the vertical, the hoist

cable would be released thus throwing the bucket beyond the reach of the crane

boom. Even though a cofferdam was

constructed at the sound end of the channel, huge pumps removed seepage and

standing water in the channel during construction.

|

| Dragline excavating a canal, photo curtiscy of North LaFourche Levee District |

|

| The State magazine, 1969 |

The canal bottom filling with sand, that migrates from the sides

soon became a serious problem. By the early 1970s a system-wide vertical bulk-heading

program was undertaken.

This dragline construction approach produced another result that

is observable today. The land adjacent to the east end canal is noticeably higher then

the otherwise natural elevation. As the dragline cranes went about their

business they produced mounds of material and high ridges that line the canal

path. In places on top of existing dunes or filling swales between dunes and in

other place running perpendicular to the natural east/east run of the

dunes.

After the East side of the waterway was completed the developers

and the Roosevelt’s were displeased with the damage this approach instilled on

the land and the nearby vegetation, particularly the mortality to both pine and

hardwood trees. A review of the condition by the School of Forestry, NC State [iv]pointed

out, “The lower water table, cuts and fills, mechanical injury, and sudden

exposure are four, any of which could place the trees under Stress.” Accordingly,

a new construction approach was employed for the West end of the waterway

system.

To avoid some of the negative impacts on the environment, AC

Davis, a local construction contractor and civil engineer suggested and

approach that employed pan scrapers and bulldozers.

|

| Typical motorized pan scraper of the era |

Some

of the advantages with pan scrapers are improved control of the depth and

condition of the excavation and better control of the placement of the dredged

material. Using the pan scraper technique one machine does the excavating,

carrying, and leveling. As the machine traverses the excavation site it scrapes

up a thin layer of material that is held in the machines hopper, when full it

travels to the dispersal sight and deposits the material in a thin controlled even

layer. This process is repeated as often as needed to attain the desired depth.

In the case of the East end canal the material was used the fill low spots and

to build up the roadways. Thus avoiding the high unnatural mounds and

unintended damage to vegetation experienced during the East construction.

Before

the dedicated motor scraper came into regular use in the 1960s, there were

smaller versions: the towed scraper, one of the first bulk earthmoving machines

invented. Nineteenth-century scrapers were drawn by horses, but were later

adapted for use with tractors and bulldozers.

After

the two parts of the canal were completed, only a small land link on which ran Mimosa

Blvd remained as the final barrier to a free flowing continuous waterway. The

original idea was to install a culvert under the roadway to allow water to flow[v]. They

decided instead, to install a bridge to allow better tidal action circulation

and permit small boaters to pass from one side of the canal to the other. A

contract was entered into with T.D.Eure Construction Co of Morehead City in May

1972 to build such a bridge. The entire contract document is shown below.[vi]

The construction schedule called for

completing the task in four and a half weeks at a cost of $20,210. (An amount similar to the cost of the bridge over the canal at Oakleaf.[vii])

As is the case with many construction projects, difficulties were encountered.

The cost remained the same, but completion took an extra two weeks. That bridge

built in 1972 was replaced in 2012, after a multi-year project, that also ran

into a few difficulties, and at a cost substantially higher.

In

addition to providing many recreational benefits, the canal system lowers the

water table, which improves the operation of everyone’s septic system, helps

drain the land, enhancing the dispersal of storm water and eliminating the need

for road-side drainage ditches. All of which contributes to keeping the

mosquito population at a tolerable level. The ownership and responsibility for

maintaining the waterway is spread among several groups. The contents of the

canal are federal/state waters, the bottom of the canal was deeded to Pine Knoll

Association by the Roosevelt family, and the bulkheads are the responsibility

of adjacent landowners as specified by town ordinance. Maintaining navigable

depth is the responsibility of PKA. In

the past PKA working in conjunction with the town, have been able to acquire state

grant moneys to partially defray the cost of needed periodic dredging. While the

natural forces that move silt to the canal continue, there is no guarantee that

state funding will be available in the future.

Contact the History Committee

[i]

Audio recording of PKS 25th anniversary, available in the archives

of the Pine Knoll Shores History Committee.

[ii]

Letter from J.W.R. Norton, M.D., State Health Director to T.F. Hearth, 18 June

1965, archives of the Pine Knoll Shores History Committee.

[iii]

Photo by Bob Simpson, as presented in Jack Dudley’s book Bogue Banks

[iv]

Letter from F.E. Whitford, Forestry, NC State University-Raleigh, 27 May 1969,

archives of the Pine Knoll Shores History Committee.

[v]Annual

meeting minutes, Pine Knoll Association.

[vi]

T.D.Eure collection in the archives of the Pine Knoll Shores History Committee.

[vii]

Henry Von Oesen & Associates Budget Estimate, Jan 26, 1966, bridge at

Oakleaf $27,500. Archives of the Pine Knoll Shores History Committee.